Does Anyone Want to Win the Premier League?

Here's how to do it: score a lot, concede a few. Two months into the season, not a single team in England can check both boxes.

Black lives matter. This document has an exhaustive list of places you can donate. It’s also got an incredible library of black literature and anti-racist texts. Donate, read, call, and email your representatives. We’re all in this together.

If you take a look at the top of the Premier League table right now, it probably won’t shock you. There sits Liverpool, defending champs, winners of 196 points over the previous two seasons -- the second-largest point haul over consecutive campaigns in the history of English soccer. I picked them to win the title again, and although they weren’t betting-favorites (Manchester City were and still are), they weren’t far behind. Seeing Jurgen Klopp atop the Premier League standings isn’t a surprise anymore.

But keep scanning across the ledger, and you’ll eventually land on a big ol’ 15. Your eyes might double-back across the first row of the table just to check: Huh, they’ve only played seven games. Seems like a lot of goals to give up. Sure is. As of Monday morning, if you traced your finger down that goals allowed column, you wouldn’t find another 15 and you wouldn’t find anything bigger, either.

Seven games into this wild Premier League season, this might be the wildest stat: Liverpool had won the most points and allowed the most goals. Put another way: the best team in the league has the worst defense in the league.

Now, Liverpool’s defense isn’t likely to continue being quite this awful. Per Stats Perform, they’ve conceded 8.28 expected goals beneath those 15 actual goals. But those underlying numbers aren’t particularly good, either, as 10 other teams have conceded fewer. Liverpool’s rearguard looks like bottom-half-of-the-table chum, and yet their ambitions and -- more importantly and incredibly -- their current reality is top of the league.

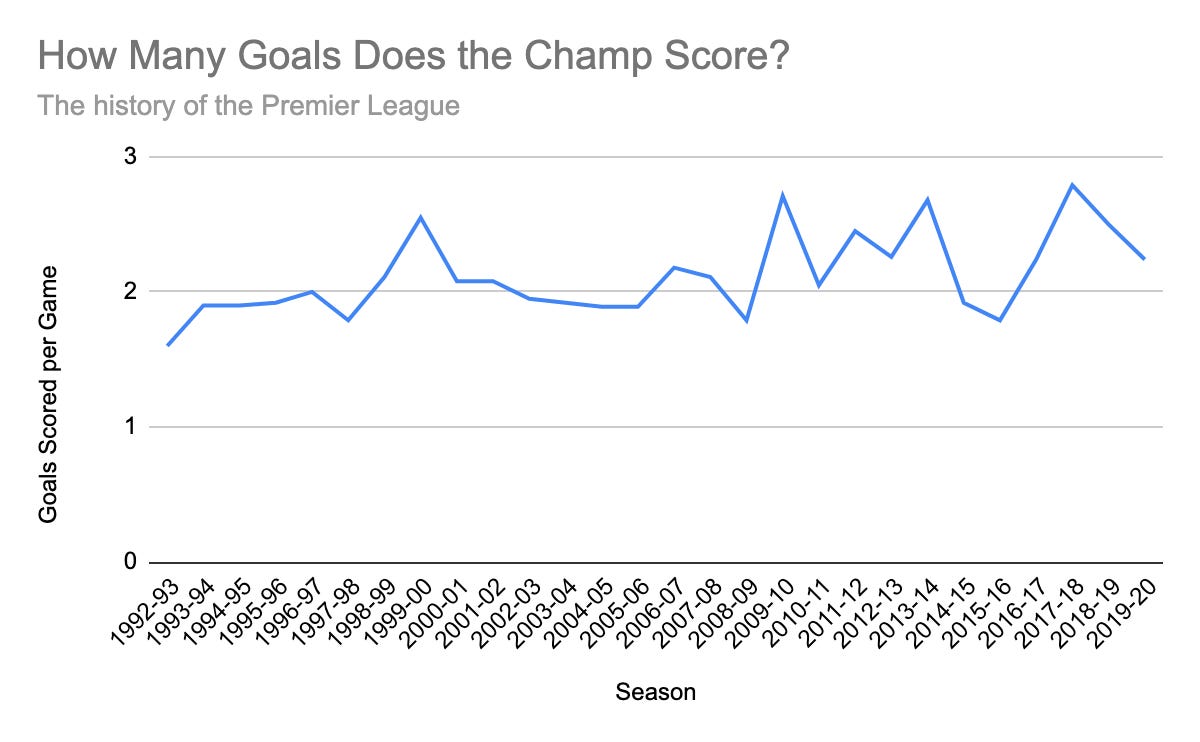

Just how bad can a title-winning defense be? Let’s take a look:

I love this chart. It’s a perfect snapshot of the three eras of the Premier League: basically “Pre-Mourinho”, “Mourinho”, and “Post-Mourinho”. Up to 2004, the league was a little more open and a little less, well, tactical. The simple 4-4-2 formation tended to rule the day and you won matches because your players outplayed the other team’s players, who were playing in the exact same formation and standing in the exact same spots on the field. Then, in 2004, hot off a Champions League trophy at the helm of tiny, unfancied, not-so-mega-club Porto, Jose Mourinho took over at Chelsea. Aided by the wealth of billionaire Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, Mourinho combined an abundance of newfound talent with painstaking defensive organization. The waves of 4-4-2s shattered against the rocks below Stamford Bridge, and Mourinho’s Chelsea allowed the fewest goals in the history of the league (0.39 per game) en route to a title in his first season with the club. Next year, they allowed the second-fewest goals in league history (0.58) as they won the league again. The next season, Sir Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United broke a three-year drought -- after winning eight of the first eleven league titles -- by beating Mourinho at his own game. Over the next three seasons, they allowed an average of 0.64 goals per game, and they won three titles.

Then came the upward climb out of the darkness, as the league’s best teams started to allow more goals in exchange for scoring more goals, too. Manchester City’s -- and to a lesser extent, Tottenham’s -- rise into Big Club status added four more tough games to the schedule and also made it tougher for top sides to grind out results at a prolific-enough clip to win the league. Throw in the growing influence of some proactive, attack-minded foreign managers, plus the Premier League’s rising wealth advantage stocking the league with attacking talent from top to bottom, and here we are today.

Over the 28 years of the Premier League, the average title-winner has allowed 0.87 goals per match. Liverpool are, uh, currently more than double and close to triple that mark: 2.14 goals allowed per match. In fact, only three title winners have ever even allowed more than a single goal per game, and all of ‘em were United sides coached by SAF: 1.13 in 12-13, 1.16 in 96-97, and 1.18 in 99-00.

Given how much the game has changed over time, perhaps Sir Alex’s final team could serve as some kind of model for Klopp’s current club? If anything, they’re more of a funhouse-mirror for the defending champs to stare into. Per Stats Perform, that United team allowed 12.8 shots per match, while Liverpool are currently allowing 8.71. While Liverpool limit quantity, United limited quality, allowing 0.08 xG per shot, which was third-best in the league in 12-13. Liverpool are giving up shots worth an average of 0.14 xG. Add it all together, though, and the two defenses aren’t that far apart, per Stats Perform: United allowed 1.07 xG per game, while Liverpool are up at 1.18.

In analytics circles, that 12-13 side is known as either A) one of the luckiest teams ever, b) one of the most confusing teams ever, or c) some combination of the two. They scored 86 goals on just 70.4 xG. For our purposes, though, it doesn’t necessarily matter how fortunate they were -- just that they scored. Those 2.26 goals per match were the seventh-most among all Premier League title winners:

The macro-story here isn’t as interesting: league-winners score a lot of goals, always have! The average champ has scored 2.1 goals per match. The league-winner low once again goes to Sir Alex Ferguson, whose Manchester United won the inaugural Premier League season with just 1.6 goals per game -- the same number as Mourinho’s sixth-place Tottenham ended up with last year. And while both of Mourinho’s first two Chelsea sides scored under two goals per match, just three of the 14 title-winners since have failed to break that threshold: Ferguson’s United in 08-09, Mourinho’s Chelsea again in 14-15 (of course), and Leicester City under Claudio Rainieri the following year. Liverpool’s current goal-scoring rate (2.43) is better than last year’s champions and better than all but six of the sides that won the Premier League.

Combine it with their goals allowed, though, and it’s still not close to a title-winning pace. With 17 goals scored and 15 allowed, Liverpool’s per-game goal differential is plus-0.26. No Premier League winner has ever been below 0.84.

This chart tracks more directly with goals scored rather than goals conceded because, well, great teams score more goals than they concede. Premier League champs, on average, outscore their opponents by 1.28 goals per game, and it’s on something of an upward trend. So far this century, only one winner has dipped below 1.00: Leicester City, maybe the least-likely champion in the modern history of professional sport and not a team you really wanna try to replicate.

For Liverpool, the elephant in the room is their 7-2 loss to Aston Villa. Strip that out of their results, and they’re scoring 2.5 goals per game and allowing 1.3 goals per game -- a defense that’s worse than any title-winner but a fantastic attack and an overall goal differential that’s not too far off of the average champion. But even with that game -- after all, it did happen -- they still look like they should start performing up to the levels of winners past: Their best-in-the-league xG differential is north of 1.00, and their xG conceded per match is the exact same as the number of goals conceded per game by the leakiest title-winner in league history: Manchester United at the turn of the century.

In fact, with scoring up all across in England, only two teams in the league currently have defensive records that wouldn’t be worse than all 28 of the previous champions: Wolverhampton (1.17 goals per game) and Arsenal (1.10). But neither one comes close to the requisite goals scored or goal-differential tallies; combined, they’ve scored the same number of goals that Liverpool have scored on their own. Meanwhile, Tottenham, Chelsea, Aston Villa, and Leicester City don’t have the defenses, and they’re all scoring and out-scoring their opponents at previously-title-winning rates -- but they’re also all outperforming their xG numbers by a significant margin, which could continue but is more likely to fall off.

One team we haven’t mentioned yet is the team that’s still favored to win this freaking thing: Manchester City, who have none of the statistical makings of past champions, whether it’s actual goals or expected. And so, we’re left with this: Through seven weeks of the Premier League season, nobody looks like a champion.