The Lost Superstars of Liverpool and Tottenham

First, Tottenham sold Gareth Bale to Real Madrid. Then, Liverpool sold Luis Suarez to Barcelona. Five years later, both clubs are in the Champions League final.

Six summers ago, Tottenham sold a 24-year-old Gareth Bale for a then-world-record fee of £86 million. A year later, Liverpool did the same with Luis Suarez, moving the 26-year-old on to Barcelona for £65 million. In Bale’s first year with Madrid, they won the Champions League. Ditto Suarez and Barca. All in all, Bale and Suarez have combined for four La Liga tiles and five Champions League trophies since moving to Spain.

As for the teams they’ve left? Taken together, Liverpool and Tottenham have ... not won a damn thing. Since Bale skipped town in the summer of 2013, Spurs lost the Carabao Cup (né Carling Cup né League Cup) final in 2015, and they finished second in the 2016-17 Premier League season. Liverpool have a couple more almost-trophy-wins: a Champions League final loss last season and a second-place Premier League finish this year, along with Europa League and League Cup defeats in 2016.

Well, one of those voids is about to be filled, as the two clubs play each other in the Champions League final this Saturday. Barring an international incident or extraterrestrial invasion, these two clubs are going to play a soccer game, one of them will win, and then one of them will become the champions of Europe.

Among players who have moved abroad from the Premier League this decade, the fees for Bale and Suarez have only been surpassed by Liverpool’s sale of Philippe Coutinho to Barcelona last January. With the recipients of all that money not just back to where they were before they let their superstars go -- but beyond it -- one might assume that savvy reinvestment of all that cash has finally paid out. One would, however, be wrong. In fact, one of the more remarkable things about both Tottenham’s and Liverpool’s achievements over the past half-decade is that they both, to varying degrees, botched their rebuilds the first time around.

During the 2012-13 season, only two players in the Premier League averaged at least five shots per 90 minutes: Luis Suarez and Gareth Bale. What made Bale’s numbers -- and sheer aesthetic performance -- especially compelling is that he did it not as a striker but as a winger/attacking midfielder. While the winger-as-de-facto striker role has become common now, this was new. Bale played with a barely-controlled kind of straight-line athleticism that made every field he set foot on seem smaller than it really was. He took 98 shots from outside the box that season -- 24 more than the next highest total -- and although that might seem anathema to the still-fledgling idea that “if you shoot from closer to the goal, you’re more likely to score”, Bale’s left-foot made sure it didn’t matter. He scored nine goals from outside the penalty area; no one else had more than five.

Bale also landed in the top 20 in the league for chances created per 90 minutes and for dribbles completed. He combined for 25 non-penalty goals+assists on the year, and the two guys after him -- Jermain Defoe (14), Clint Dempsey (13) -- were both in their age-29 seasons.

So, considering they had to replace a player who did everything for them and the aging supplementary players beside him -- Defoe and Dempsey would soon both be playing in MLS -- perhaps it’s not surprising that Tottenham tried to replicate the Welshman with seven different players. David Rudin summarized the moves well for Statsbomb a couple months ago:

In short, Spurs turned their Bale money and some spare cash into seven new signings, none of whom cost more than 30 percent of the Bale fee. Since nobody remembers what nine-figure fees meant in 2013, it’s helpful to think of what comparable fees netted in the Premier League that summer. Let’s remember some guys:

Roberto Soldado and Erik Lamela, the two biggest purchases, each cost a bit less than Marouane Fellaini and a few million more than Stevan Jovetic and Alvaro Negredo.

Paulinho’s transfer fee ranked between those paid by Chelsea for André Schurrle and Southampton for Dani Osvaldo.

Christian Eriksen basically cost Spurs as much as Cardiff City spent on Gary Medel.

Étienne Capoue’s acquisition was equivalent to Simon Mignolet’s move to Liverpool.

Vlad Chiriches cost Spurs about £500,000 more than Cardiff paid them for fellow center back Steven Caulker. His fee was tantamount to what Southampton spent on Dejan Lovren and Norwich spent on Ricky van Wolfswinkel.

Nacer Chadli’s price matched what Liverpool spent on each of Tiago Ilori and Iago Aspas and Aston Villa spent on *squints at notes* Libor Kozák.

Where are those guys now? Well, Roberto Soldado is playing for Fenerbahce in Turkey, where he scored six goals and assisted four more this season because he JUST TURNED 34 YEARS OLD. That means that Spurs signed him when he was 28, or already at the tail-end of his prime. The move was basically indefensible at the time, and it still worked out worse than anyone could’ve expected: Over two seasons with Tottenham, Soldado, a striker, scored one non-penalty goal in the Premier League.

Among the others, Paulinho started 31 Premier League games across two seasons and is currently on his second stint in the Chinese Super League. Capoue is coming off a really nice Premier League campaign ... for Watford. Chiriches started 24 games over two seasons in London; he’s made 10 starts over the past two years for Napoli. And while Chadli lasted for three years at Tottenham, he spent last season playing for West Bromwich Albion, who were relegated, and this season playing for Monaco, who were two points away from being relegated.

The two signings that worked out were the two that seemed the smartest at the time. Eriksen and Lamela were both promising prospects with varying levels of early success, and maybe most importantly, they were both 21 -- with years to go until they even hit their primes. (None of the other signings were under 23.) Lamela hasn’t exactly fulfilled his promise. Here’s what Ted Knutson wrote for Statsbomb back in the summer of 2013:

I think Lamela is the best young forward in Europe ... Primarily a left-footer, he played inverted this season for Roma and was hugely productive out there on the right. Key passes, dribbles, strong LOP stats (Loss of Possession), passing percentage, and even Shots on Target… every damned thing you can think of is outstanding. And then there’s the goal rate, which matches up well with the very best in Europe already, at age 21.

That sounds ... a lot like Gareth Bale. Lamela’s attacking output (15 goals and four assists for 0.66 NPG+A/90) for Roma was ninth-best in Italy the season before he moved to England. He hasn’t turned into an attacking centerpiece -- his five goals and nine assists (0.53 NPG+A/90) in 2015-16 are still his best marks in each category -- and he’s often been hurt, but he’s contributed plenty of minutes for a team that consistently qualifies for the Champions League. An added benefit of signing a young player with Lamela’s sky-high potential is that even if he doesn’t hit it, he’s still likely to be a useful player for a long time.

Although he cost less than half of what Lamela did, Eriksen is the one who actually became something like a centerpiece. He’s started all but nine Premier League games since Mauricio Pochettino became manager in 2014, and he’s registered at least five goals and 10 assists in each of the past four despite often occupying a deeper midfield position. If the rumors are true, he’ll soon become the club’s next Bale, a Madrid-bound star who brings in a massive fee. If not, well, Eriksen’s still a year younger than Soldado was when Tottenham signed him.

For as good as Bale was, Suarez was even better the next year. He scored 31 goals on zero penalties, while adding in 12 assists. He also only played 33 games ... because he was suspended for the first six games of the year after ... biting Chelsea’s Branislav Ivanovic during a match the previous season. Mohamed Salah broke Suarez’s record for goals in a 38-game season with 32 just last year (in addition to 10 assists). However the fact that Suarez did it without the aid of penalties and despite missing five Premier League games makes his 2013-14 season, in my opinion, the greatest in the Premier League era. His per-90 minute production (1.31 non-penalty goals+assists) is the best the league has ever seen.

Much like Bale, Suarez’s production and playing style were irreplaceable. At his peak, the Uruguayan seemed to playing at a tempo between chaos and control that no one else on the field could ever access. A seemingly bad touch would entice a defender to make a tackle, and suddenly the ball was through his legs. A bouncing ball 40 yards fromof goal seemed like it needed to be controlled, and suddenly it was being volleyed into the upper corner.

However, the Liverpool Suarez left was also a much better team than the Tottenham that lost Bale. They’d just finished in second. Daniel Sturridge, with his 22 non-penalty goals and six assists, was coming off one of the better non-Suarez attacking years in league history at just 23. Raheem Sterling was the third “S” in the attacking trident and had played over 2,000 minutes at age 18. Behind them, Coutinho and Jordan Henderson were just about to enter their primes, and their energetic presence in midfield had allowed 33-year-old Steven Gerrard to experience a late-career renaissance as a playmaker (14 assists) deep in midfield.

And so, undiscouraged by the mixed-at-best results from Tottenham’s approach, they decided to take it a step further and sign eight players. Among Premier League teams, Liverpool bought five of the 20 most expensive players that summer -- most of any team -- but just one was in the top 10, at 10th.

That would be Adam Lallana for €31 million from Southampton -- sandwiched right between Premier League legends Eliaquim Mangala and Juan Cuadrado on the most-expensive list. It always seemed like an odd move: Lallana was the same age as Suarez -- meaning 1) that his timeline didn’t quite match up with the team’s young up-and-comers, and 2) Liverpool would only be getting the tail end of his peak -- and he was also an attacking midfielder who wasn’t particularly good at the two things an attacking midfielder is supposed to do: creating goals and scoring them. Lallana thrived in Jurgen Klopp’s first two seasons with the club as a converted midfielder (where his lack of goal threat wasn’t an issue), but he’s started just six games over the past two seasons.

In a funny way, Pochettino influenced much of Liverpool’s immediate post-Suarez plan. His Southampton side impressed then-manager Brendan Rodgers enough that the club not only brought in Lallana; they also signed Dejan Lovren (€25.3 million) and Rickie Lambert (€5.5 million) that same summer. Lovren never quite looked comfortable in Liverpool’s backline until Virgil van Dijk arrived last January, and it’s likely not a coincidence that the team cut its goals against total from 38 to 22 in a season where he went from starter to third- or fourth-string. Lambert, meanwhile, was 32 when he signed, scored two goals and assisted two more in his one season with the club. He retired from soccer two seasons ago.

As for the others: Lazar Markovic, a 20-year-old attacker from Benfica, seemed like potentially the savviest signing of them all -- a youngster who no one had heard of but who’d earned consistent game-time for a Champions League team. It turns out the was unknown because he wasn’t very good; he hasn’t played a game for the club since his first year, and he spent this season at relegated Fulham, making a solitary appearance off the bench. I’ll admit to being stupidly hyped about Mario Balotelli: He’d already had multiple seasons of elite attacking production for really good teams, he was only 23, and €20 million was a low risk. After a bizarre first season (one actual goal on 5.24 expected goals), he hasn’t played a game for the club since.

Poetically -- for this specific exercise -- Balotelli’s first start for the Reds came against Pochettino’s Spurs. In what was a false dawn for this set of players, Liverpool ran Tottenham off the field, in a decisive 3-0 win:

That game included what was also probably the highlight of Alberto Moreno’s Liverpool career. Then-a-22-year-old fullback, he came over from Sevilla for €18 million. He started the majority of the Premier League games in his first two seasons with the team, but he’s made just 18 starts over the past three seasons -- or: the era when Liverpool started qualifying for the Champions League again.

The best of the signings was 20-year-old Emre Can for €12 million from Bayer Leverkusen. He became a starter in midfield or as a backline-hybrid pretty much right from the jump. He kept playing consistently once Klopp came in ... until the final couple months of last year. Strangely, the club let his contract expire, and now he plays for Juventus. The other signing in the Can mold as a then-19-year-old Divock Origi from Lille in France. He is, undoubtedly, an infallible god. Perhaps even the infallible God. But despite his divine nature -- and his two goals against Barcelona in the Champions League semi finals -- he’s started four Premier League games over the past two seasons.

It’s not just that Liverpool never found their own Eriksen; they might not have ever found their own Lamela, either.

Liverpool and Tottenham have become two of the best clubs in the world, not because of the way in which they replaced their superstars, but in spite of how they did it.

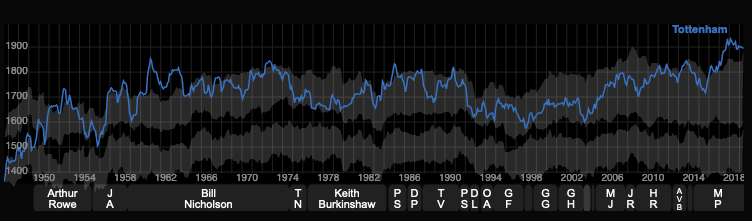

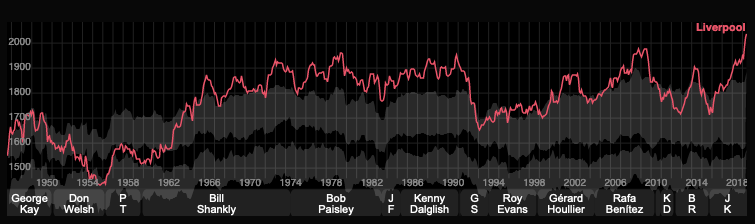

According to the Elo ratings, which remain the best publicly available method of comparing clubs over time, Liverpool currently rate as 1-B with Manchester City, while Tottenham sit in fifth, behind those two, Bayern, and Barcelona. On the day Bale signed with Madrid, Tottenham were 11th and Liverpool were 19th. On the day Suarez went to Barca, Liverpool were eighth and Tottenham were 20th.

The most obvious reason for why these two teams have shot way beyond where they were with their two stars is that they landed two of the best managers on the planet.

Here’s the Pochettino effect:

And here’s Klopp:

The thing that connects Poch and Klopp (and every other great manager) is that they make their players better. Whether that’s by tactics, training, motivation, an inherent understanding of the Zodiac calendar, a pact with a a dark lord, etc., players plug into the Tottenham and Liverpool lineups and perform better than they ever have before. Fullbacks from Hull City and Burnley become attacking fulcrums, a guy from League One becomes a superstar as soon as he steps on the field, and a Chelsea washout turns into the Egyptian Messi.

And yet, despite their ability to improve their charges, Klopp and Pochettino have wanted almost nothing to do with most of the players their clubs brought in to replace Bale and Suarez. Of the 15 guys Liverpool and Tottenham acquired in the summers of 2013 and 2014, just a single one, Eriksen, is expected to start the game in Madrid.

The thing Tottenham and Liverpool have both achieved is a kind of exponential success, where everything builds on itself.

You hire Klopp, and you invest in analytical edges. You identiy the right players, and he makes them better, and your team improves, and you qualify for the Champions League, and you make more money, and you can afford and entice even better players, who the coach will then make better, and now you’re at the top of the game.

Tottenham, of course, haven’t signed anyone since last January, so it doesn’t quite work like that, but they’ve shown just how far a young core paired with a great manager can take you. Harry Kane, Heung-min Son, Alli, and Eriksen have all been with the team since it least 2016, and their average age is just a smidge over 25. Combined, they cost £45.12 million. Per Transfermarkt, all four of them have market values north of that, at a total of £400 freaking million. A group of players steadily improving year after year makes misses in transfer market less costly, it makes it easier to build out the fringes of the roster, and it allows the manager to tweak the game-by-game approach around them. It also lets you take a year off from adding news players in order to build a new stadium and still manage to finish top four and run all the way to the Champions League final. You can improve, even if you stand relatively still.

The game on Saturday, then, is a symbol of how these two clubs have transformed since they lost two generational talents. Part of the reason they both found it hard to spend the money from the Bale and Suarez sales is that they couldn’t convince the big-money players they could now afford to come to their clubs. Tottenham had just finished in 6th, and although Liverpool were hot off a second-place season, their main transfer target, Alexis Sanchez, chose Arsenal over Merseyside. But thanks to better coaching, decision-marking, and rising broadcast revenue, that’s no longer the case. After the 2012-13 season, neither club was among the 10 wealthiest in the world. Today, they’re both there.

The players they have now are less likely to leave -- and even if they do, they’re both positioned to recover, and even improve on, the loss. Liverpool sold Coutinho last January for more than either Bale or Suarez, and they essentially replaced him with Virgil van Dijk and Allison, perhaps the best defender and best keeper in the world. They didn’t get worse; they got better. And if Tottenham do lose Eriksen this summer, they’ll still have Kane, and Son, and Dele. They’ll have a new stadium, and whoever they sign -- assuming they start doing that again! -- will be stepping into a side that already has a number of other stars in place and a manager -- assuming he stays! -- that’ll know what to do with him.

Whoever wins on Saturday will be the team that brings this whole thing full circle. For the first time since 2013, neither Gareth Bale nor Luis Suarez is going to lift the European Cup.