Your European Soccer Crib Sheet

We're about halfway through the season. If you're just emerging from your nuclear fallout shelter -- which, same -- here's your update.

First issue/volume/blog/newsletter/newslettito/canto/stanza/commandement whatever! Thanks for subscribing — the initial response has been incredible, and I’ve barely provided anything of value so far. As I said in the initial post (which does not get held up to the same kind of jargony scrutiny because it was not e-mailed to anyone), the structure of this thing will be somewhat fluid over the first few weeks as I figure out what works well, what makes the most sense, and what you all like best.

So, for today: three things about European soccer, all of which I find interesting! Since this is the first one of these, I’m gonna stretch all the way back to the beginning of the current campaign (mid-August) and survey the scene for some broad takeaways. If you’re an alien just arrived to Planet Earth who wants some context for what’s happening this soccer season — and you just so happen to speak English and have an innate understanding of concepts like “play,” “competition,” and “capitalism” — then I’m here to help. And if you’re not from outer space, I guess I’m here for you, too.

The Great Teams Aren’t Great Anymore

At The Ringer, the last piece I wrote was about how the three teams that dominated the last decade of European soccer had suddenly stopped dominating. This was less than 10 games into the season, and — as will be a constant theme around these parts — soccer is extra-random compared to all the other sports, which are just very random, so there was some danger in declaring anything definitive about Barcelona, Bayern Munich, or Real Madrid so early on. Taken together, these three clubs have won seven of eight Champions League titles and 13 of 16 Bundesliga and La Liga championships, but in mid-October they were winless in 10 combined matches. I sketched out the factors behind their potential declines — aging rosters, inexperienced managers, new money elsewhere — and F.C. Hollywood’s American Twitter account got mad at me, online:

Well, two months later, the trend lines are still pointing downward. Just this past week, Real Madrid lost a Champions League game at home by a 3-0 scoreline for the first time ever. They’ve already fired the coach who they forced to get fired in order to hire — the now-double-disgraced former Spain manager Julen Lopetegui — and they’re in fourth place in Spain with only a plus-4 goal differential through 15 games. Barcelona, meanwhile, are currently in first place, six points up on Madrid and three points up on second-place Sevilla and Atletico Madrid. On the surface, perhaps, things seem to be humming along in Catalonia, but lift up the hood, and you get a face full of smoke.

Given all the variables that go into scoring a goal, and given how few goals there are in a soccer game, things like “total points” and “goal differential” only really tell you a partial story about a team. So, enter: expected goals (xG), a statistic that puts a conversion probability on every shot a team takes and concedes (based on loads of historical data that takes into account things like location, body part used, and the pass that led to a shot). If you take 10 shots with a 10-percent chance of converting, you end up with an xG of 1.0. Basic team-level soccer philosophy is this: The side that creates the better chances won’t win every game, but it’ll win most of the games. Getting that balance in their favor is what pretty much every team, at any level, is trying to achieve. Expected goals, then, is an effort to show who’s creating the best chances and conceding the worst ones. And when it comes to doing those things, both Barcelona and Real Madrid have fallen off a cliff:

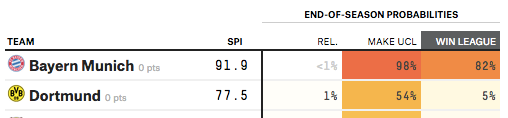

As for Bayern, they’re nine points back of first-place Borussia Dortmund after a 3-2 loss to the league-leaders last month. Coming into the season, Bayern were the overwhelming favorites to win the Bundesliga title, per FiveThirtyEight:

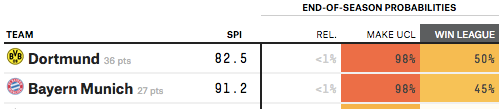

Today, they’re, uh, yeah, about that …

Of course, the German giants could mount a comeback, Barcelona could stretch their La Liga lead beyond danger before February, and Real Madrid could win their fourth Champions League in a row. (Or, as I wrote about for Slate today, they could all break off and form their own league.) But right now, none of those things are likely, like they always used to be. Competing against these three clubs for the past decade — the top-level star power of Madrid, the Lionel Messi-led brilliance of Barca, and the incomprehensible talent-depth of Bayern — has been like competing against the four fundamental laws of nature. Maybe you temporarily avoided gravity for a moment, but it always, eventually, slammed you back to Earth. That’s not the case anymore, though, and it’s changing the lens you have to use to look at the world-soccer landscape in real-time. I don’t think anyone will be afraid of playing any of these teams once the knockout round for the Champions League starts (draw’s on Monday). With gravity gone, someone else might just float to the top.

Liverpool Are The Best Team in England, But They’re Not as Good As Manchester City

Sixteen games into the Premier League season, Liverpool are undefeated, and Jurgen Klopp’s activewear is to 2018 what Brian Clough’s sweaters were to the 1970’s. (Told you this thing would not lack for knitwear talk!)

Liverpool have 13 wins and three draws — good enough for 42 points, the third-most at this stage in the season in Premier League history. The two teams ahead of them, 17-18 Manchester City and 05-06 Chelsea, both won the English title by a combined 27 points. Last year, Klopp’s team, which finished fourth, would often blitz its opponents into oblivion by creating as much chaos as possible and banking on the fact that they were better at dealing with all the upheaval than anyone else.

That style led to three breathtaking victories against Manchester City, the best team in Premier League history, and pushed the Reds all the way to the Champions League final. (As a Liverpool fan, I was as disappointed as anyone that they canceled that game against Real Madrid and left the title vacant for a year, but continental governing bodies are a fickle bunch!) However, since Liverpool fired every match into a frenzy, there still seemed to be massive downside potential to most of their games: If they could beat anyone, they could also lose to anyone. When you set the field on fire, there’s always a chance you’re the one who gets burnt. This year, though, they’ve slowed things down at times, and oh yeah, they paid €60.5 million in the summer for Alisson, an extremely handsome Brazilian keeper who keeps saving their ass whenever the defense breaks down. They conceded a goal per game last year; this year, it’s down to 0.38. In fact, not a single team in Europe’s top five leagues (England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain) has conceded fewer goals than Liverpool’s six.

So, title-party here we come?!?!? Probably not.

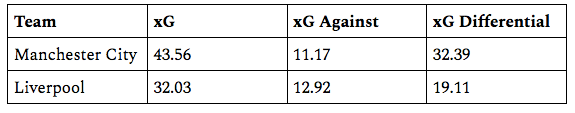

The fourth-best 16-game start of the Premier League era belongs to this year’s Manchester City, who are currently one point back of Liverpool and who were two points ahead of Liverpool before last weekend’s 2-0 loss away to Chelsea. City have scored 11 more goals than Liverpool, and they’ve conceded just three more. Here’s how the xG matches up:

In other words, if Liverpool hadn’t given up a single shot this whole season, City would still have created a better balance of chances. That’s absurd, but xG isn’t the be-all-end-all — no number is. Certain players can out-perform their underlying stats for a season, much like in baseball, or football, or basketball, because of their talent or just because they get hot. And the reason a team like Liverpool spends so much money on a goalkeeper is, essentially, for him to break the concept of xG: to concede fewer goals than the average keeper would. So far, that’s been the case:

However, Manchester City are bankrolled by the United Arab Emirates, coached by Pep Guardiola, who’s the best manager the world IMO, and they have what’s probably the deepest roster out there, with multiple top-five-at-their-position Premier League players at pretty much every spot on the field. It doesn’t seem reasonable to expect Liverpool to out-talent them over a 38-game season.

This is not to say that Liverpool don’t have a real shot at winning the Premier League. They do: 34 percent, according to FiveThirtyEight. In most other years, they’d be huge favorites at this point, but in most other years there hasn’t been a team like City standing in the way. In fact, the only other time was last year, when City won the league by 19 points. Hell, Liverpool might even be the second-best team in Europe for all we know — the FiveThirtyEight rankings model currently thinks so. They just happen to be in the same league with what seems like the best team in the world.

Kylian Mbappé’s World Cup: Not a Fluke

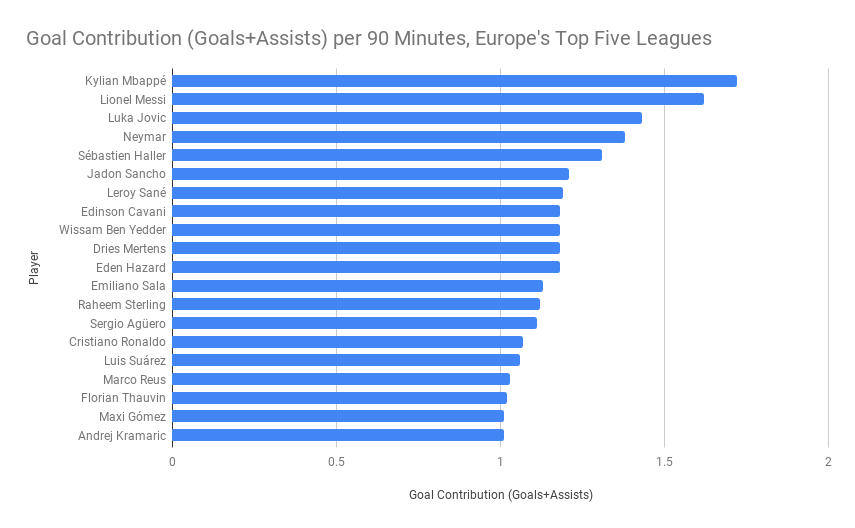

Remember that wild child who vaporized Argentina and high-fived Pussy Riot in the middle of the biggest sporting event on the planet? Well, he’s picked up right where he left off. These numbers, which only include players who have logged at least 800 minutes so far this season, come from Football Whispers, and I stole the visualization idea from Michael Caley:

A couple simple ways to get a better feel for how productive an attacking player is: 1) add up his/her goals and assists, 2) compare that to the number of minutes he/she has actually played. Upon doing so, you realize that a freaking 19-year-old has been the most productive top-level attacking player on the planet so far this season. He’s averaging 1.72 goals+assists per 90 minutes. Those numbers are slightly inflated by the lesser quality of the teams at the bottom of the French league and also by the fact that PSG, who currently have a 13-point lead in Ligue 1, are so much better than everyone else. But guess why PSG are so much better than everyone else: Because they have Mbappé, who, again, IS BARELY OLD ENOUGH TO BUY CIGARETTES IN ALASKA. At the World Cup, Mbappé was devastating in the open field, but on a dominant team like PSG, space is at a premium because opponents don’t try to contest possession and instead drop deep to defend their own goal. Mbappé is on the path to becoming the best player of his generation because of an uncanny ability to move at full-speed, in full-control, through tight space that I’m not sure I’ve ever seen before:

A couple other interesting names on the list: Borussia Dortmund’s 18-year-old British winger Jadon Sancho (1.21) and Eintracht Frankfurt’s practically ancient 20-year-old Serbian striker Luka Jovic (1.43). Then in second on the list, of course, you’ll see the 31-year-old Messi (1.63), who hasn’t been below 1.20 in a season since Mbappe … was eight years old. This season is still young, but seeing the two of them at the top of this list is a fun little kaleidoscope of sorts, giving us a glance into the present, the past, and the future all at once.

As I said last time: If you enjoyed this, please subscribe! And please pass on the word to anyone you know who might be interested. Call your boyfriend. Tell your girlfriend. Inform your mortal enemy. Everyone is welcome … unless you’re a fascist — in which case, get the hell outta here! Thanks, as always, to all you non-fascists for reading along.