Frenkie de Jong and the Mystery of Midfield

Why haven't de Jong, Rodri, and Tanguy Ndombele had bigger impacts for their new teams?

Three of the four most expensive midfielders of all time changed teams this summer. And no Zinedine Zidane didn’t come out of retirement. Granted, I’m not convinced Zizou couldn’t still play. His post-retirement exploits, after all, are the reason why the US didn’t qualify for the 2018 World Cup. He ruined a generation:

He’s also not a midfielder -- in the traditional sense. Soccer’s going through a bit of the same positional revolution that every other sport is; delineations have begun to disappear, and the better your team is, the harder it is to tell your positions apart. Even some of the NFL’s most effective quarterbacks, perhaps the most defined position in all of sports, are taking on responsibilities outside of what they’d traditionally been asked to do.

But if your main tasks are some combination of “scoring goals” and “creating goals” then, at least for the exercises of this issue, you’re an attacker. Think someone is an “attacking midfielder”? Just stop after the first six letters and add a stutter. The names for whom that procedure applies: Philipp Coutinho, Zidane, James Rodriguez, Angel Di Maria (twice), Kevin de Bruyne, Thomas Lemar, Kaka, Luis Figo, and Oscar.

And so, there’s Paul Pogba atop the list -- the ultimate example of a player who can at least do a passable job at all the traditional midfielder tasks while also scoring and assisting at an impressive clip -- followed by the three guys who switched teams this summer: Barcelona’s Frenkie de Jong, Manchester City’s Rodri, and Tottenham’s Tanguy Ndombele. Both Rodi and Ndombele were club-record buys, and Frenkie fetched a higher fee than either of them.

And yet, a month or so into the season, none of them have made much of a difference. Midfield is hard position to quantify, and it’s even harder to play.

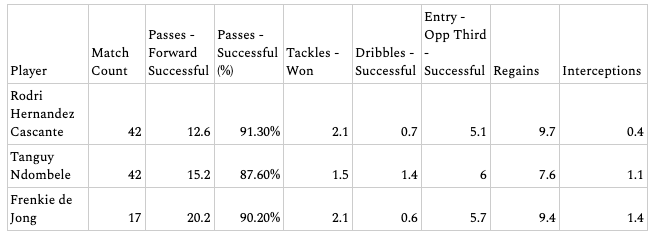

Per Stats Perform, here’s what the three midfielders did last year -- Rodri with Atletico Madrid in Spain and the Champions League, Ndombele with Lyon in France and the Champions League, and Frenkie with Ajax in the Champions League.

And here’s what they’ve done for their new teams:

For Rodri, the on-ball production has ticked up a tiny bit. He’s making more vertical passes, pushing the ball into the attacking third more frequently, and winning the ball back more often -- all seemingly effects of playing for the best team in the world. Ndombele’s doing roughly the same amount of ball-winning, but his passing has dropped off. And as for FDJ, he’s less actively defensively, making fewer forward passes, but also working the ball into attacking areas way more often -- a function of playing for a team that’s kept more possession than any other team in Europe so far this season.

There’s nothing glaring in any of those numbers. If anything, it’s kind of interesting that they all changed teams and are still producing in roughly the same patterns. So, in other words, three of the most promising midfielders in the world swapped clubs, kept doing all of the things that made them so promising in the first place ... and none of them made their teams better. On the whole, City are still an indomitable machine -- they’re taking more shots than any team in Europe’s Big Five leagues and they’re conceding fewer than every team other than Getafe -- but they’ve allowed 10 Big Chances in six games. They allowed 35 in 38 games last year. Tottenham, meanwhile, have the ninth-best attack (by expected goals) and the 10th-best defense in the Premier League. And as for Barcelona? Listen to yesterday’s podcast; they’ve got the seventh-best attack and defense in Spain. Hopefully Lionel Messi doesn’t have a relegation clause.

So, what gives? For starters, most soccer players tend to have a smaller impact on winning than they do in, say, basketball. Here’s how it was once explained to me: The average PL championship team tends to win around 85 points, and the average relegation teams tend to land around 30 points. That’s a 55-point gap; there are 11 players in the field; so the average distance between the best players in the league and the worst players in the league comes out to about five points over the course of an entire season. If relegation teams are made up of the ol’ “replacement-level player”, then the best players in the league are worth around five or more points above replacement.

On top of that, at least according to the transfer market, midfielders are the least valuable players on the field. Among the 20 most expensive players of all time, there’s Pogba, then there’s 15 attackers, one keeper, and three defenders. I’ve cited this paper before, but the researchers recently updated it, so I’m citing it again. Here’s the question it tries to answer:

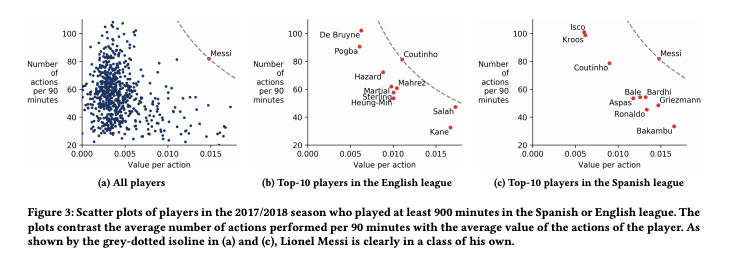

How will a soccer player’s actions impact his or her team’s performances in games? This question is relevant for a variety of tasks within a soccer club such as player acquisition, player evaluation, and scouting. It is also important for the media and building fan engagement, as fans like nothing better than comparing players and arguing why their favorite player is better than the others.

Nevertheless, the task of objectively quantifying the impact of the individual actions performed by soccer players during games remains largely unexplored to date. What complicates the task is the low-scoring and dynamic nature of soccer games. While most actions do not impact the scoreline directly, they often do have important longer-term effects. For example, a long pass from one flank to the other may not immediately lead to a goal but can open up space to set up a goal chance several actions down the line.

To answer it, they assign a value on each action over the course of a game, based on how likely it is to lead to a goal and to prevent a goal, and then add ‘em all up to create an approximation of player value. These were the results from the 2017-18 season:

What you’ll notice: FIFA got it right, and barely any midfielders are on there! And the ones who do appear -- Pogba, Toni Kroos, and fine I’ll give in and include KDB’s 17-18 season, too -- are guys who accrued their value through a ton of low-value actions.

However, the paper only looks at on-ball actions, and most of a midfielder’s responsibilites come without the ball. It’s providing support for a pass to relieve pressure, it’s cutting off passing lanes into the opposition attack, it’s occupying space to draw out a defender. That third aspect is the focus of another paper I’ve mentioned a number of times, the one written by Luke Bornn of the Sacramento Kings and Javi Fernandez of FC Barcelona. The paper looks at which players during a specific Barcelona match were particularly adept at creating and occupying valuable space on the field. The main findings:

Through the analysis of a first division Spanish league match, we show a handful of approaches to better understand a missing key factor for performance analysis in soccer: off-ball attacking dynamics. The quantification of space occupation gain and space generation allows us to observe Sergio Busquets’ high relevance during positional attacks through his pivoting skills, the dragging power of Luis Suarez to generate spaces for his teammates, and the capacity of Lionel Messi to occupy spaces of value with smooth movements along the field, among many other characteristics.

Sergio Busquets! He’s a midfielder! That ability to find space wouldn’t appear in any kind of publicly available counting statistics -- no matter how advanced they are -- and most clubs likely haven’t even begun trying to figure this out, either. But, the idea tracks: Sergio Busquets has been an ever-present on a number of the best teams in soccer history, despite not racking up any kind of eye-popping numbers. Yet, his presence on all of these teams clearly suggests that he contributes significantly to winning.

Midfield value isn’t always hidden, though. Before he got hurt, Pogba was leading United in passes into the final-third AND passes received in the box, while also playing a large role in moving the ball into the box and receiving passes in the attacking third, too. That’s a heavy load for one player to carry -- there are, I don’t know, maybe three other players in the world capable of doing it -- and without Pogba for the past two games, United’s attack has predictably lost whatever edge it might’ve had: just 19 shots, 2.32 expected goals, and one actual goal.

Beyond that specific and unique example, it’s really hard for any player to immediately impact his team’s fortunes over a five- or six-game stretch. The Premier League season is six games old; and based on that rough 5-point rule, the best players will have improved their teams by about 0.8 points over that stretch -- a barely perceptible effect, especially when we don’t know even know what each team’s baseline necessarily is, either.

Midfielders, by their nature, have an even less perceptible effect on their team’s performance; it’s the hardest position to drop into and immediately make your team better from. Attackers just have to score and create, while defenders and keepers just have to prevent their opponents from doing the opposite. Midfielders, though, have to do a little bit of everything, and perhaps more importantly, they need to have playing relationships with everyone on the field. Those relationships take time to develop, but the highly systematized approaches of most top teams now demand that they do. A great midfielder is readily accessible to every player on the field if he’s positioned properly, while attackers and defenders are a band removed from each other. There are simply fewer players to learn to consistently play with in attack and defense, but a midfielders actions and positioning affect everyone else in the eleven.

Remember, Fabinho, who’s now the ever-present defensive midfielder for the defending European champs, didn’t become a full-time starter until late 2018. And perhaps this is why, back in August, Tottenham manager Mauricio Pochettino said of Giovani Lo Celso, the club’s other big-money midfield signing, “He's training well but is still so far away from what we expect from him. We need to give him time.” The same likely holds true, then, for Ndombele, and Rodri, and De Jong. Their impacts might become apparent, but likely not until next year, or maybe even some time after that.