Hurry Up and Watch Ajax Before They're Gone

Why Monday was a bad day for Real Madrid and a good one for a bunch of milennials in Amsterdam

One team has won three Champions League titles in a row. One of their players was just awarded the prestigious Ballon d’Or, a literal golden ball that the weekly magazine France Football gives to the supposed best soccer player in the world each year. (OK, quick intermission: This year was the first year France Football also gave the award to a woman. Norway’s Ada Hegerberg won, and she was promptly asked by the ceremony’s host, a French disc jockey by the name of Martin Solveig, if she would be willing to twerk on stage. She declined. Hegerberg, who plays for Lyon in France, was then later referred to by France’s Antoine Griezmann as “that girl from Lyon”. Hergerberg, it should be noted, will not be at the World Cup this upcoming summer because the 23-year-old felt that the Norweigan federation did not treat its men’s and women’s teams equally and so she decided to retire from international soccer. After what happened at the Ballon d’Or ceremony, how can you blame her? Tl;dr Men are trash, smash the patriarchy.) They’ve spent at least $20 million on an individual player transfer 38 different times, and they currently have one of the three most valuable squads in the world (per Transfermarkt).

Before this year, the other team hadn’t made it out of the Champions League group stages since before Zinedine Zidane head-butted himself off a soccer field forever. The last time they had a Ballon d’Or winner, neither you, your parents, or your grandparents had heard “Hey Jude”. And the last time they bought a player for $20 million … will also be the first time.

At yesterday’s draw for the Champions League Round of 16, which kicks off in mid-February, these two teams were matched up with each other. It’s bad news—for the rich guys.

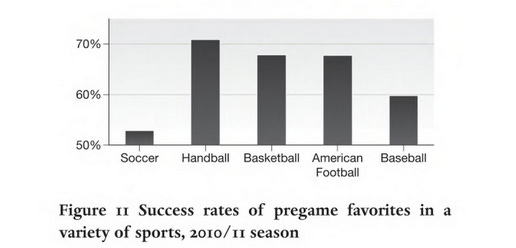

Soccer is random—I told you to get used to this kind of talk—but we’re all outcome-biased, so when a team wins a game or a tournament, we tend to look back for things that confirm that their victory was assured all along, no matter how unlikely it was. The easiest way to show how much variance there is in soccer comes from gambling. The more random the sport, the less likely the betting favorites are to win, and in soccer, the betting favorites barely even win half the time. This graph comes from Chris Anderson and David Sally’s book The Numbers Game:

Soccer’s governing bodies throw even more variance into the mix with the way they structure their tournaments. Rather than seeding all participants from no. 1 to no. Whatever — stacking the dominoes in order and then seeing how they fall — most competitions will create tiers of teams based on some complicated rating system and then form the groups or brackets by picking plastic balls out of gigantic bowls. Soccer has an obsession with holding event “draws” where they pack a bunch of bureaucrats into an auditorium and then ceremonially pair teams together by drawing lots. I guess it’s a way for people who aren’t players to briefly feel important? The Champions League, the annual competition between the best club teams in Europe (read: the world), is especially afflicted: There’s a draw for the 32 teams in the round-robin group stages, then there’s a draw to decide the single-elimination matchups in the Round of 16, then there’s another draw for the quarterfinals, and another draw for the semifinals, and at this point I’m surprised there isn’t a draw to inform the two semifinal winners who they’ll be playing in the finals.

The deterministic “If you wanna be the best, you gotta beat the best” thinking still often gets applied to these draws whenever an upstart side gets matched up with an especially difficult opponent—as if one team was always going to win it all, no matter who they played along the way. But the draw really does matter in a sport with so much game-to-game noise. Just last year, Liverpool, the fourth-place team in England, made the final thanks in no small part to drawing FC Porto in Round of 16 and Roma in the semis — two teams they were heavily favored against. This year, at least according to FiveThirtyEight’s predictions, Ajax, the second-place team in the Netherlands, were the biggest beneficiaries of the draw … because they drew Real Madrid, winners of four of the last five Champions League titles.

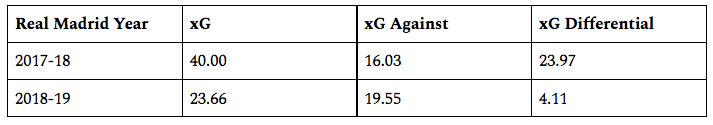

So, uh, what the hell? Well, a large part of that comes down to what we — sure, I am the one writing, but newsletters are a collective form of communication, to my mind! — talked about last time: Real Madrid kinda stink. At least, for Real Madrid they do. Through 16 games, their attack without Cristiano Ronaldo, who’s now in Italy with Juventus, is wheezing for air, and the defense has deteriorated, too.

In La Liga, Real’s goal differential is plus-five. In the Netherlands, Ajax’s goal differential—hold on, we’re gonna need a bigger font …

AJAX’S GOAL DIFFERENTIAL IS PLUS-50

Now, the Dutch Eredivisie is nowhere near as good as Spain’s La Liga. (PSV, who finished last in their Champions League group, also have a plus-50 differential.) In fact, how to translate performance in the Netherlands to performance elsewhere in Europe has been a long-vexing problem for decision-makers across the sport. Luis Suarez scored 36 goals in his last season with Ajax, and then went on to win the Premier League Player of the Year award with Liverpool and a cabinet full of trophies with Barcelona. In his last season with Heerenveen, Afonso Alves scored 34 goals, and then went on to score 10 Premier League goals in two seasons before cashing out early and joining the de-facto-retirement-home Qatari league before turning 27. Scouting the Netherlands can be a crapshoot, and as a friend who does consulting for various European clubs put it when I asked him about Ajax yeterday: “Dutch league is garbage tbf.”

However, that friend also said, “Half the world seems to want their players though, so there's that.” Ajax is so good at developing talent that 10 years ago, which feels like three centuries ago in terms of general-interest American media’s stance toward soccer, The New York Times Magazine sent Michael Sokolove to Amsterdam to write about their secrets in a fantastic piece called “How a Soccer Star Is Made”. The club also holds a special place in the hearts of many soccer fans because of its role as the incubator of “Total Football” — the revolutionary playing style that required positional interchange between all 10 field players. Everyone had to be able to attack and defend, much like they now do at most of Europe’s top clubs. Given that ethos, the youth prospects Ajax produces often play with a lovable kind of exuberant over-confidence that you really do need if you’re ever gonna be a defender who thinks he can dribble like a winger.

My admiration for the 21-year-old center-back/center-mid/center-of-the-universe Frenkie de Jong is well documented, but here’s another great compilation of what makes him such a tantalizing talent:

Then there’s Matthijs de Ligt, the 19-year-old traditional center back who just won the Golden Boy, which is not actually a boy made of gold but is given to the best under-21 player in Europe, and who might be an even better prospect than De Jong. Lifehack: Depending on your tolerance for musical artists who go by names such as “Bassnectar”, you might wanna just click that mute button before watching any YouTube soccer-skills compilation.

Meanwhile, David Neres is 21 years old, born in Brazil, and could keep a soccer ball under control in outer space:

There’s even more compelling talent—Hakim Ziyech hasn’t met an impossible dribble, a 60-yard pass, or a 30-yard shot he didn’t like—and among the 100 most valuable rosters in the world, Ajax, with an average age of 23.5, have the youngest squad of them all. They keep possession (61.4 percent) more often than all but four teams in Europe’s top five leagues, and they take more shots (21.1) than any of them.

That won’t continue forever, though. Ajax can’t compete financially with most of the teams in those top five leagues: Currently ranked as the seventh-best team in the world by FiveThirtyEight’s model, Ajax made something like €90 million per their most recently available accounts. West Bromwich Albion, which finished in last place in the Premier League last season and is currently ranked 124th by FiveThirtyEight, took in more than €150 million. And so, Ajax eventually have to sell off their best young players, or risk them walking away for free once their contracts run out. (In case you’re not familiar: soccer teams can “sell” a player to another team. In other words, rather than making a player-for-player trade, a team like, say, Barcelona, will pay Ajax $50 million for the right to sign one of its under-contract starlets. The move, however, doesn’t happen unless the player agrees to it. Yes, the artificial market for soccer players is absurd.) It’s doubtful that de Jong or de Ligt are on the team beyond this season, and a handful of their teammates will eventually follow them up to one of the bigger, more-lucrative leagues, too. “I think that is the purpose of Ajax, to develop players and bring them up to the first team as young as possible,” then-Ajax manager Martin Jol told Sokolove back in 2010. “And then we sell them, not for peanuts but for a lot of money.”

In an alternate universe, maybe one with a salary cap and a not-quite-as-open market for talent, this Madrid-Ajax match-up would be an opportunity for the new guard to deliver the knockout blow to the reeling old guard. But that’s just not how it works with European soccer. In our current reality, the time horizons have been warped in the opposite directions, making February’s match-up both incredibly important and totally ephemeral: Against Real Madrid, this iteration of Ajax will get its first and last chance to throw a punch before everyone leaves and joins the old guard.

As I said last time: If you enjoyed this, please subscribe! And please pass on the word to anyone you know who might be interested. Call your boyfriend. Tell your girlfriend. Inform your mortal enemy. Everyone is welcome … unless you’re a fascist — in which case, get the hell outta here! Thanks, as always, to all you non-fascists for reading along.