Yep, Lionel Messi Is Still Better Than Everyone Else

The best ever is the best alive, but how much longer will he last?

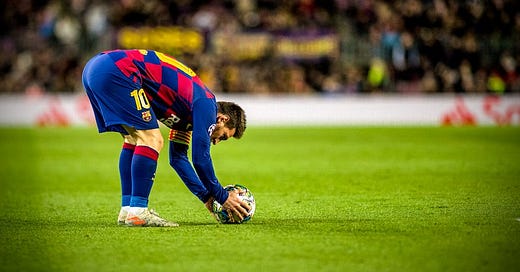

Lionel Messi did this on Saturday:

Lionel Messi also did this on Saturday:

Lionel Messi has done both of these things more than not just any other player, but more than any other collection of professional players:

It extends all the way back to the beginning of the decade, according to an article on the official Barcelona website, titled “Extraterrestrial Messi”:

Messi alone has scored more free kicks since the 2011/12 season than any other team in the big five European leagues. Not players. Teams! Messi has converted 29 in La Liga, while everyone at Juventus combined have scored 27, Real Madrid have 23, Roma and Olympique Lyonnais have 21 and PSG have 20.

There are no words to describe what that means!

Two weekends ago, Messi did this:

And in between, he did this:

Despite missing a handful of games at the beginning of the season to foot and adductor injuries, Lionel Messi is back. And for the third year in a row I can throw this sentence construction at you: Lionel Messi is supposed to be getting worse, and instead, at [insert age], he might be better than ever before. These are all his seasons, per FBRef.com, sorted by his non-penalty goals+assist rate.

Right now, he’s sandwiched between the two seasons in which he averaged ... 48 goals and 13.5 assists. Another thing about those two seasons: he was 24 and 25, theoretically the first two years of an attacking player’s prime. The thing about this season: He’s 32, a year older than the person who is writing this newsletter and who sprained his Achilles and hyper-extended his right knee the last time he tried to play 90 minutes of soccer in a single evening. Among players who have played at least 500 minutes domestically, no one else is north of 1.40 in Europe’s Big Five Leagues. No one in Spain is even above 1.00. Messi is tied atop La Liga with 12 goals+assists. His co-leader, Karim Benzema, is having another elite season without Cristiano Ronaldo in Madrid; Benzema’s also played 400 more minutes than Messi.

Back in February I wrote a similar version of this same article. In it, I looked at the percentage of shots Messi was taking and creating for Barcelona -- a “usage rate” of sorts. At the time, he was at 60 percent. This year ... he’s at 59 percent.

Second behind Messi on that list was Atletico Madrid’s Antonie Griezmann, who, of course, now plays for Barcelona. Despite playing on a team that averages the fourth-most possession of any team in Europe and offers plenty more opportunity than the defend-and-counter approach of his former club, Griezmann is averaging fewer shots (2.2) and chances created (0.8) than in any season at Atletico. I’ve at least considered the idea that Messi’s preeminence both makes it harder for players to play him and harder to play without him -- his skills require everyone else to take lesser roles than their talent is capable of filling, and then when he’s gone, they don’t know how to play when everything isn’t going through him. Except, Griezmann kinda deflates that theory, as he came from a different club and played a number of games without Messi to start the year.

Instead of helping lighten Messi’s load, Griezmann, like all of his new teammates, seemed to just add to it. The 32-year-old is leading Barcelona in shots, chances created, dribbles, and passes into the penalty area, per data from Stats Perform. In addition to doing everything around the goal, he’s also doing a significant amount of work moving the ball into the attacking third in the first place. In the graph below, all the way to the right is Jordi Alba, then two midfielders: Sergio Busquets and Frenkie De Jong. I bet you can guess where Messi sits ...

So far this season, Messi’s one of only two players in Europe who averages at least two shots, two chances created, one dribble, five final-third entries, and four penalty-area entries per 90 minutes. (The other player is Lazio’s Luis Alberto, a former Liverpool prospect who’s become one of the most under-appreciated players in Europe.) Messi’s dribbling numbers are down in La Liga from last year: 1.7 per 90, compared to 3.8 last season. But you can expect that to come up, eventually. After all, he’s at 5.4 per 90 in the Champions League -- first among all players with at least three appearances in the competition.

Yet, rather than maximizing Messi’s final years as a irreplicable, omnipotent attacking force, Barcelona have managed to build a team that’s slowly decaying around him. For the three years FBref has expected goals data for, Barca’s xG created per game has declined with each successive season: 2.00 in 17-18, 1.84 in 18-19, and now 1.68 this season. They’re taking just south of 12 shots per match this season -- tied for 57th-most in Europe with the likes of Union Berlin, who were playing in the German second-tier at this time last year, and Espanyol, who have scored seven goals so far this season. Since the beginning of the decade -- i.e. the time for which there’s publically available Opta data -- Barcelona have never taken fewer than 13.5 shots per game in a full campaign, and in most seasons they’ve been north of 15.

Across 16 games in the Champions League and La Liga this year, Barca have already been held to under 10 shots six times. Two of those games didn’t feature Messi, one saw him come off the bench, and another saw him subbed off at halftime due to injury. In the seven games he didn’t start, Barcelona averaged 1.57 points per match. In the nine matches with him on the field at the opening whistle, that number shoots up to 2.44. In both of the matches Messi started and Barcelona didn’t win, he still attempted more than half of the team’s shots.

I’ve written a lot about Messi recently -- why he’s the best finisher in the world, what things he isn’t the best at , and now this. Maybe that’s too much, but every time I look up his stats or watch one of his games, I find another thing that blows me away. I’ll see a pass I didn't know he still had. Or I’ll catch him on a Saturday, turning free kicks into lay-ups. Or I’ll mess around and make another chart that doesn’t require a label:

The more time I’ve spent writing and thinking about soccer -- trying to figure out why the sport lags so far behind others in terms of strategic creativity; why it’s so hard to sit down, watch a game and really know why one team won -- the more aware I am of how damn hard it is. As someone who got filtered out at the final step before the pro level, I’m probably uniquely aware of how difficult soccer is, but it’s not necessarily immediately obvious at the highest level. I bang on about how random results can be, how something like expected goals paints a better picture of how a game went than the straight-up scoreline. The reason that’s true? It’s not easy to put a ball into the back of the net without using your hands! The Europe-wide conversion rate sits right around 10 percent; Messi’s double that, but even he’s only scoring with one out of five times. When the greatest soccer player of all time takes a shot, it rarely goes in.

The low-probability precision applies to everything else, too. Take Liverpool’s second goal on Sunday. Here’s all it took to happen -- a perfect pass from Trent Alexander-Arnold, a perfect touch from Andy Robertson, a perfect run by Sadio Mane to open up space for the cross, a perfect ball from Robertson, a perfect run from Roberto Firmino to drag Fernandinho just far enough away from Mohamed Salah, and a perfect header from Salah on a bouncing ball while he’s running at full speed.

If the calibration on any of those things is just slightly off, then the goal never happens. You can say the same thing about most goals, most shots, most passes, most teams that defend well, most of anything that comes off across a 90-minute match -- so many different people and actions have to aligned for something successful to happen, and even then, it’s still not a guarantee because there are 11 other players trying to destroy whatever you’re trying to do.

Performance seems so precarious, and yet Messi has been dominating every phase of the attacking game for my entire adult life. Liverpool needed a bunch of players to be perfect at just one or two things in order to score that goal -- and plenty have mastered one or two aspects of the game over the years and become some of the best players in the world. But Messi has made a career of doing all of those things by himself, and doing them as well as anyone ever has. From a piece I mentioned earlier — about how Messi’s the best goal-scorer of the modern era:

Since 2014, he has completed more than 300 through-balls; next best is 173. He leads all players in assists, and he's second in dribbles. He's as good -- if not better -- than every other player alive at facilitating attacking possession, breaking down a defender and creating for teammates. But even if you removed all of that and reset those totals to zero, he'd still probably be the best player in the world.

It’s amazing that he ever did it; it’s unthinkable that, at age 32, he’s still doing it. So, until he stops, I’m gonna keep writing, and we should all keep watching -- watching him carry this flawed Barcelona team, watching him try to win his first Champions League title since 2015, but really: just watching him at all.