Still working my way through the COVID-relief donation requests, nearly a year on. There were a lot! This one is for McKinley, who requested a piece about Gareth Bale.

On Sunday, Harry Kane and Son Heung-min broke a record that had been standing for 25 years. Back in 1994-95, Alan Shearer and Chris Sutton combined for -- or: assisted each other on -- 13 goals. Behind the league’s most dynamic duo, Blackburn nipped just one point ahead of mighty Manchester United to win the Premier League title. Until Leicester’s improbable run in 2016, Blackburn were the only team other than both Manchesters, Arsenal, and Chelsea to finish the season atop the standings of modern English football’s top division.

While not quite as reliant on a single pair, Leicester’s success was also driven by their own special twosome. Riyad Mahrez assisted on five of Jamie Vardy’s goals, while three more came in the opposite direction; no other pairing in the league ranked in the top 15, both ways.

While dollars have almost always equaled destiny in the Premier League, one grand theory behind breaking the connection between revenue and table ranking could be: build your team around getting the best out of a pair of complementary super-skilled players with a near-telepathic understanding of each other’s movements. Earlier in the season, it seemed like Spurs themselves might be able to follow a similar path to their first-ever Premier League title, with Kane turned provider to Son’s red-hot right and left feet -- but it wouldn’t last.

There’s probably a reason why that record they broke lasted for 25 years, too: duos are all but dead. The top teams today all play with somewhere between a front three and a front five, saturating as much area across the final third as they can and making their possession play way less predictable than if it all ran through two guys. With a pairing, you only get two possible passing connections: A to B and B to A. With a trio, you get six: A to B, B to A, A to C, C to A, B to C, and C to B. It’s why all the great attacking units of the past decade are thought of in threes: Firmino, Mane, and Salah; Sterling, Suarez, and Sturridge; Messi, Suarez, and Neymar; Benzema, Bale, and Ronaldo.

He’s a little late to the party, but Jose Mourinho might’ve finally found his third man -- formerly Tottenham’s main man.

If anything, the fact that Son and Kane broke the Shearer and Sutton’s record in early March undersells how reliant Spurs have been on their two stars. Take a look at this chart, compiling all of Tottenham’s non-penalty goals and assists:

The reliance on Kane and Son also shows up, pretty simply, in how much they’ve both played. Of the players FBref’s Statsbomb data classifies as having played some minutes in a “forward” role, here’s how the minutes have shaken out:

Bergwijn, Moura, and Lamela have taken up the majority of Tottenham’s third-forward minutes: 2,488, more than either Son or Kane have played so far. The three of ‘em have combined for just six goals and assists. That shakes out to about 0.02 goals+assists per 90 minutes, and that rate of production would be the 222nd-best rate among all qualified players in the Premier League this year.1 Kane, meanwhile, is leading the league with 1.07 G+A/90, and Son is second at 0.85. In other words, Tottenham’s front three this season has mainly consisted of the two most productive attackers in the league and ... the worst attacker in the league.

He’s only played 500 minutes, but Gareth Bale, who re-joined his former club on loan from Real Madrid over the summer, has already changed all that -- to an absurd degree. As you’ll see above, despite just making five starts in the league this season, Bale is already Tottenham’s most productive non-Kane-or-Son attacker. In an extremely limited share of minutes, Bale’s averaging 1.26 G+A/90. That would be tops in the league and Messi-esque over a full season, but although he’s running way above his underlying totals -- 0.70 xG+xA per 90 -- those underlying totals would still be third-best in the league this year, after Kane and Kevin De Bruyne. With the way Bale has played since re-entering the starting lineup at the end of the last month, Tottenham’s third-forward spot has undergone just about the largest upgrade imaginable: worst player in the league to one of the best.

Could Bale have done this from the jump? And can he keep it up? The first one is impossible to answer, and it’s probably not worth trying to dig too deep into it. Here’s Mourinho’s take on the matter:

I found psychological scars. When you have a couple of seasons with lots of injuries I think it is not about the muscular scars but the psychological scars -- that brings fears and instability. There is a moment when you are working very well and everyone around you is giving everything we can give, there is a moment where that psychological barrier has to be broken. And he broke it. It was him, not us. We just supported him.

OK, Amerigo Vespucci of the mind. I’d be inclined to believe Mourinho -- he has more information than I do, after all -- if he didn’t have a history of benching previously great players who then continued to be great once they were un-benched, be it under an acquiescent Mourinho or Mourinho’s managerial replacement. That’s not to say Bale would’ve lit the league on fire from the get-go, but rather: the other options were all so bad that it basically would’ve been impossible for Bale to have performed any worse. Given what he’s shown so far and that he’s been a top-10 player in the world for much of the last decade first at Tottenham and then at Real Madrid, re-integrating Bale a couple months ago would’ve had a significant upside with almost no downside.

After getting throttled by Manchester City, 3-0, in mid-February, Tottenham’s top-four odds, per FiveThirtyEight, dropped down to 11 percent. Since then, Bale’s played 249 league minutes, scored four goals, and assisted two more. Their top-four odds have since risen up to 25 percent, and the Sporting Index betting market projects them to finish fifth -- a point ahead of Liverpool and 4.5 points behind fourth-place Leicester, who Spurs play on the last day of the season.

A 31-year-old Bale isn’t the force of nature he used to be -- wrecking games by sheer force of momentum. And his long injury history means he could disappear faster than he reappeared. But Spurs don’t need him to be anything close to the Bale he used to be. The fourth goal against Burnley was a nice little encapsulation of where he can fit in, and how he’s changed over time:

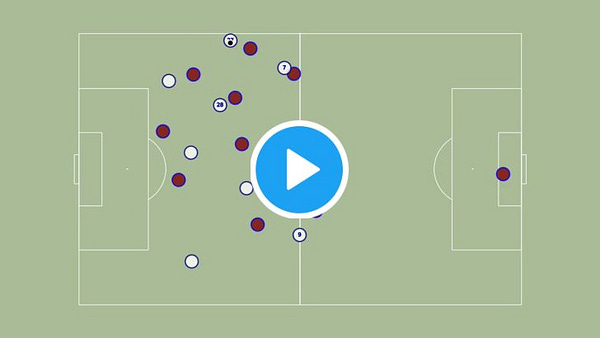

Rather than funneling the play through Bale from start to finish, all the ball progression comes down the left side, as the Welshman just hangs out in space, pushed up on the right wing, biding his time. As Son drives forward and plays the ball into Kane, Burnley’s defense gets sucked over to the Son-Kane combo because that’s where the ball is but also because that’s where all of Tottenham’s goals come from.

In the 24 previous games, shutting down those two -- forcing them to move the ball elsewhere -- would’ve meant shutting down Tottenham. Instead, now there’s Gareth Bale, streaking into the box, wide open, planting the ball past the keeper, and reminding everyone that, yeah, three really is better than two.

To qualify for the rate-stat leaderboard, a player needs a, per FBref: “Minimum 30 minutes played per squad game”.